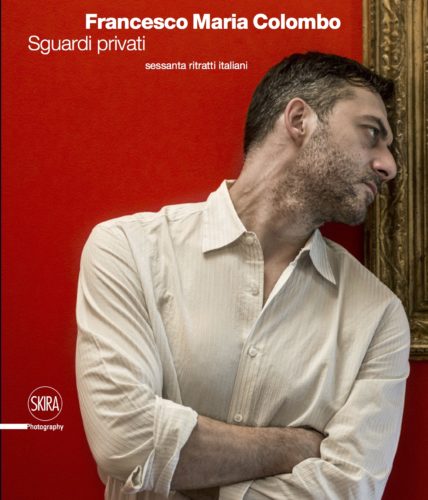

«Sixty portraits including black and white and colour. Solids and voids. Silences and tremors. Francesco Maria Colombo’s approach to photography is meditative, because he observes his subjects slowly, leaving them free to express themselves in the time and the space they prefer. These images seem to reveal to us the last act of a quest that follows, explores and flushes out his subject until the latter chooses to yield to the camera lens. In a certain sense these portraits express the idea of the inner drama and deep intimacy that the subjects chose to tell in photography. It is as though they expected from the “wonderful discovery” the purest representation of themselves, focusing on the figure of the photographer-interpreter of man and life. Each portrait of the series seems to tell a secret». (Denis Curti)

«Sessanta ritratti, fra bianco e nero e colore. Fra vuoti e pieni. Fra silenzi e sussulti. L’approccio alla fotografia di Francesco Maria Colombo è di tipo meditativo, perché osserva lentamente i suoi soggetti lasciandoli liberi di esprimersi nel tempo e nello spazio che preferiscono. Queste immagini sembrano svelarci l’atto finale di una ricerca che segue, esplora e stana il suo soggetto fino al momento in cui sceglie di aprirsi all’obiettivo della macchina fotografica. In un certo senso, questi ritratti esprimono l’idea del dramma interiore e dell’intimità profonda che gli stessi personaggi scelgono di raccontare in fotografia. È come se dalla “scoperta meravigliosa” essi si aspettassero la rappresentazione più pura di se stessi, ponendo l’attenzione sulla figura del fotografo-interprete dell’uomo e della vita. Ogni ritratto della sequenza sembra svelare un segreto». (Denis Curti)

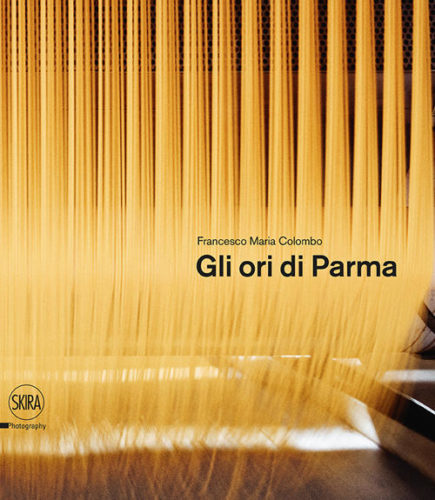

Gli ori di Parma

A photographic account of the food produced in Parma is a risky venture. On the one hand there is the persistent myth of the “homemade”, of ancient and skilful handiwork; on the other, the industrial reality with its production system, food-processing techniques, and machines far removed from the collective imagination. Francesco Maria Colombo has investigated the icons of memory and gone into the factories to discover the invisible protagonist in the industrial process: the human hand, the worker’s daily labour. His is a photographic journey that reveals the complexity of a whole world ltered through the eye of the narrator and the “cultural” perspective of the art informel avant- garde. And, as Gloria Bianchino writes in her introductory essay, he has photographed “the culture of art through that of food, which, from an anthropological point of view, is the same thing.”

Il racconto fotografico del cibo prodotto a Parma è una scommessa rischiosa. Da un lato resiste il mito del “fatto in casa”, dell’artigianato antico e sapiente; dall’altro vi è la realtà dell’industria, con il suo apparato produttivo e le tecniche di trasformazione del cibo: vi sono le macchine, rimosse dall’immaginario collettivo. Francesco Maria Colombo ha indagato le icone della memoria ed è entrato nelle fabbriche per stanare il protagonista invisibile del processo industriale: la mano dell’uomo, la quotidiana impresa di chi lavora. Il suo è un viaggio fotografico che fa emergere la complessità di tutto un mondo, filtrandolo attraverso l’occhio del narratore e la prospettiva “colta” delle avanguardie informali. E fotografando, come scrive Gloria Bianchino nel saggio introduttivo, «la civiltà dell’arte attraverso quella del cibo. In una prospettiva antropologica la stessa cosa».

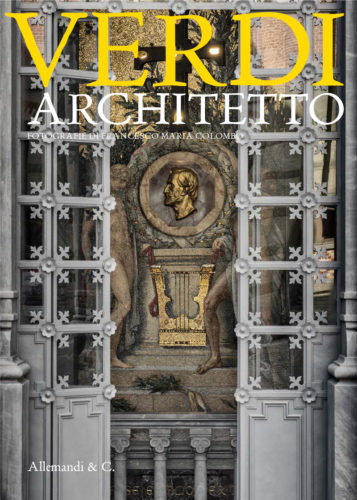

Verdi Architetto

“Verdi became an Architect and I cannot describe to you, during the work, the waltzing of beds, chests of drawers and all the furniture!…” This is what Giuseppina Strepponi wrote to Countess Maffei in 1867. In Verdi’s bicentenary, on discovering how the composer became designer, furnisher, farmer, agronomist, benefactor, builder of houses for himself and others, we can view the greatness of a Father of the Nation from an unfamiliar angle. Today in Villa Sant’Agata, in the Hospital of Villanova sull’Arda, in the Retirement Home for Musicians of Milan (“my most beautiful work”), we are still enfolded in memories, nostalgias, echoes, the mysterious afterglow of Verdi’s music. With a musician’s sensitivity, Francesco Maria Colombo sought out these atmospheres and fixed them through the camera lens. The essays by Carlo Majer and Alessandro Turba complete the historical reconstruction and recognise in the Verdi “inventor of spaces” the complexity and modernity of a genius not confined to music.

«Verdi si trasformò in Architetto e non ti posso dire, durante la fabbrica, le passeggiate, i balli dei letti, dei comò e di tutti i mobili!…». Così scriveva Giuseppina Strepponi alla contessa Maffei nel 1867. Nell’anno bicentenario verdiano, scoprire come il compositore si sia trasformato in progettista, arredatore, fattore, agronomo, benefattore, edificatore di case proprie e altrui, permetterà di cogliere la grandezza di un Padre della Patria secondo una prospettiva inconsueta. Nella Villa di Sant’Agata, nell’Ospedale di Villanova sull’Arda, nella Casa di Riposo per Musicisti di Milano («l’opera mia più bella») siamo ancora oggi avvolti da memorie, nostalgie, echi, misteriose scie della musica verdiana. Con sensibilità di musicista, Francesco Maria Colombo è andato alla ricerca di queste atmosfere e le ha fissate attraverso l’obiettivo fotografico. I saggi di Carlo Majer e Alessandro Turba completano la ricostruzione storica e nel Verdi «inventore di spazi» riconoscono la complessità e la modernità di un genio non confinato alla musica.